National Truth & Reconciliation Day or, Orange Shirt Day, as it is more commonly referred to, is slowly starting to become a part of the national consciousness and that has to be a good thing on many levels. Sadly, it took the discovery of children's graves on the grounds of residential schools to finally give us a collective wake-up call but it worked. Through the story of a little 6 year old girl, who had her new orange shirt stripped off and taken away on her first day at the Mission school, we now have a recognizable symbol for the movement that is now engaged in a wide range of initiatives seeking redress for past wrongs.

And it's about time, because ignoring the abusive and discriminatory treatment of First Nations people is turning out to be a very expensive head-in-the-sand approach. The horrific, well documented, and ongoing saga of the residential school abuses has at long last wound its way through the legal system and survivors have been collectively awarded $3 billion in compensation. A further $23 billion was later awarded to First Nations for the discriminatory underfunding of Child and Family Services programs and to implement the Jordon's Principle, a child-first, needs-based policy to provide access to all government funded services to all First Nations children whether they live on or off a reserve.

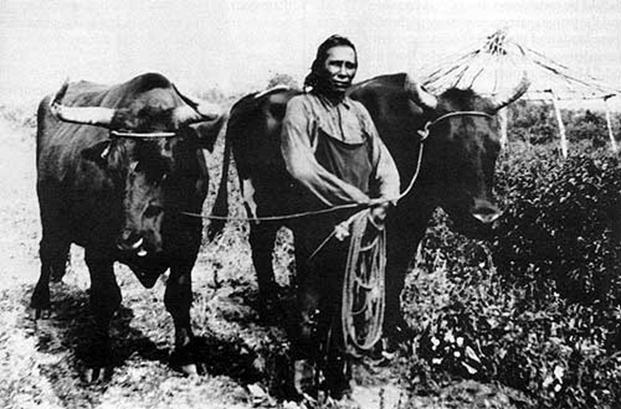

In the 1870's, when the so-called numbered treaties 1-7 were being signed to provide land for settlers on the prairies, reserves were also set up for the First Nations people, along with the provision for seeds, some tools, and supplies in the event of crop failure. The reserves were to enable them to make the transfer to an agricultural way of life now that the bison had been wiped out and, in the beginning, many of the First Nation farmers were quite successful. However, their success soon led to settler animosity and, in 1889, the government introduced the Peasant Farm Policy which restricted the types of tools First Nations could use, how much they could grow, and what they were allowed to sell. Farms were reduced to 40 acres, machinery was forbidden, and all planting and harvesting had to be done by hand. These policies soon put most of the First Nations farmers out of business and their reserve farmlands were then sold by the government to new settlers because the government claimed they weren't using the land properly.

As much as 20% of First Nations reserves were illegally sold off by the government between 1896-1911 and this continued up until the 1930's. To make matters worse the money collected by the government on the land sales wasn't always turned over to the band it belonged to. However, in recent years lawsuits were filed against the government to contest the illegal surrender of reserve land and, more than $3.5 billion has since been awarded to 56 claimants. This past August the Muscowpetung Saulteaux Nation alone was awarded $150 million, the maximum allowable.